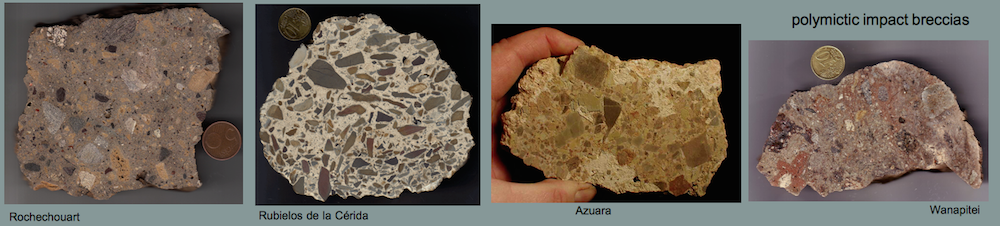

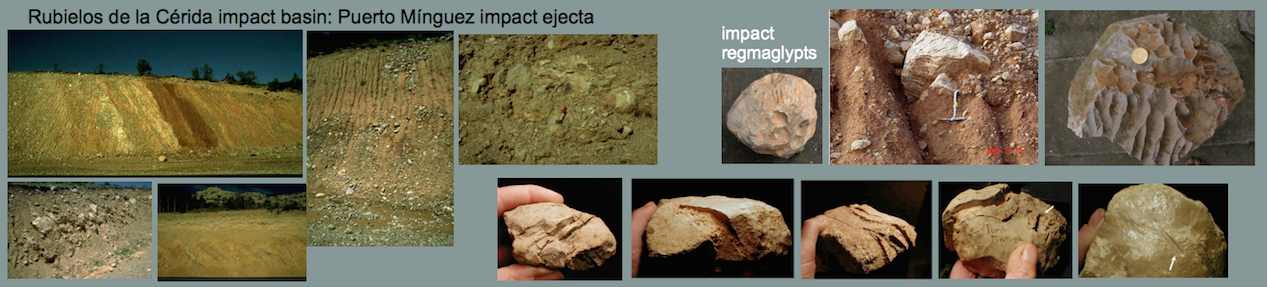

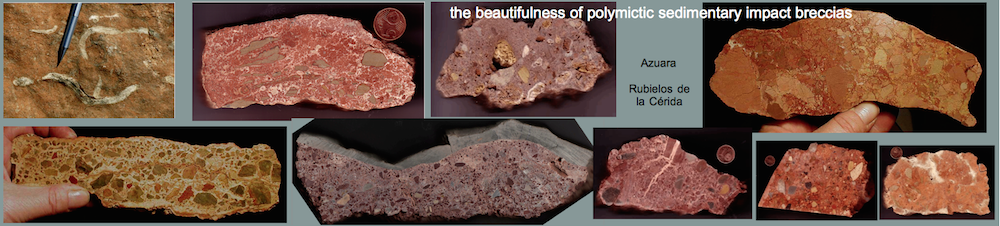

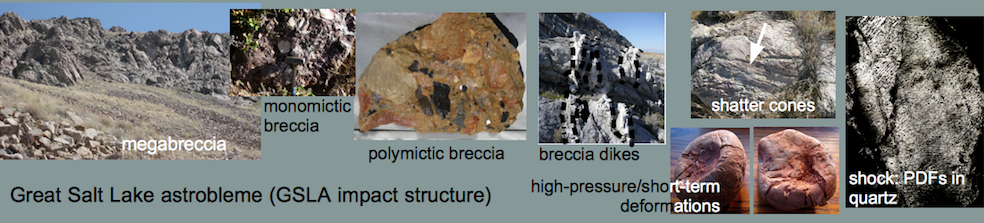

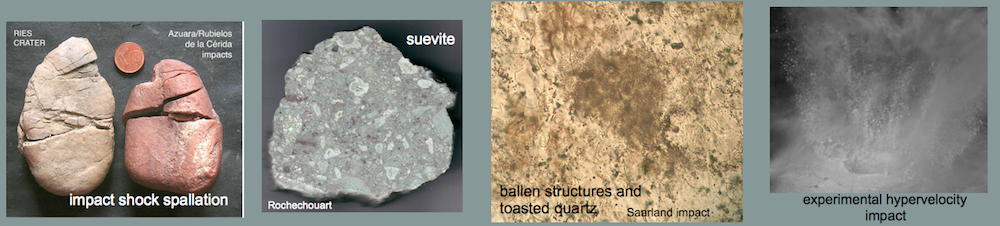

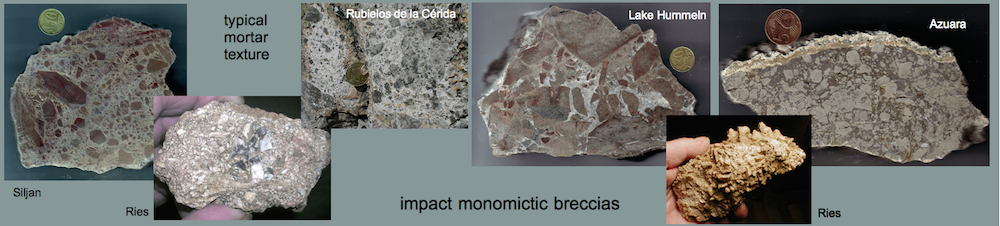

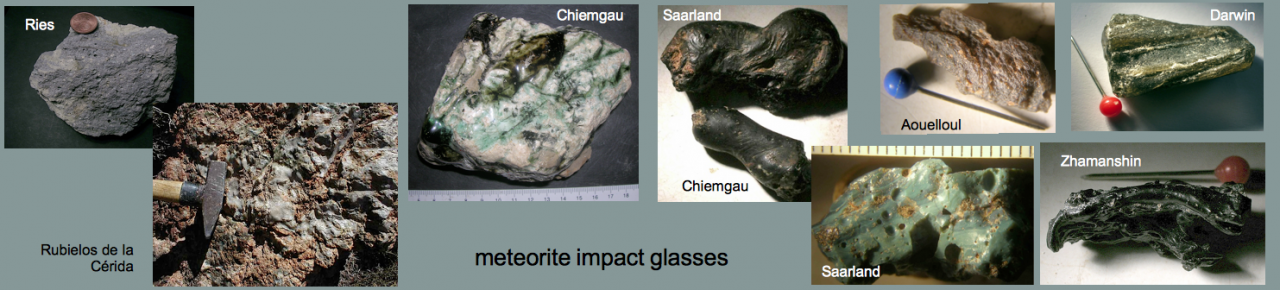

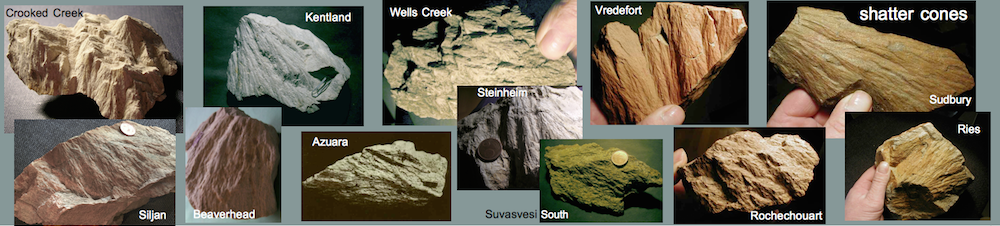

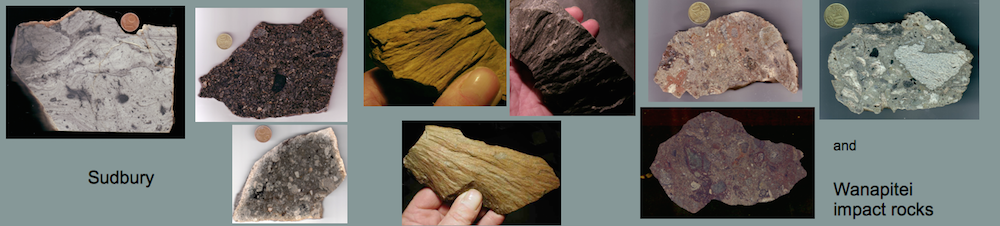

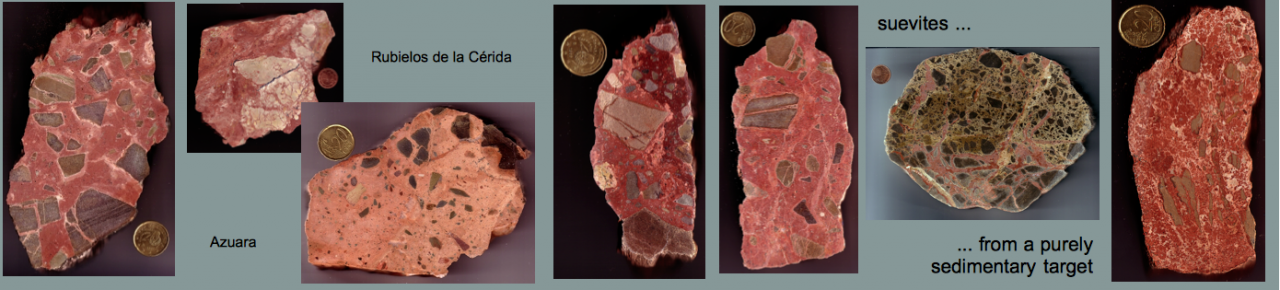

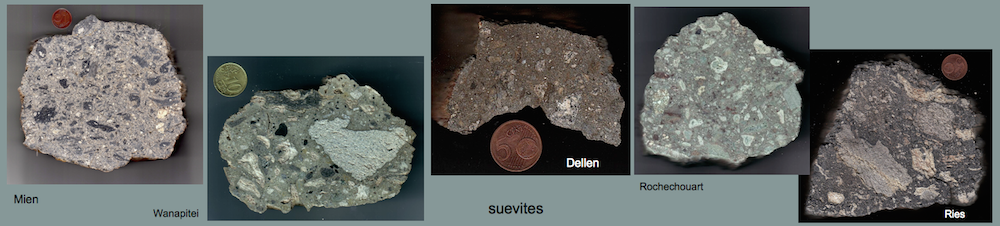

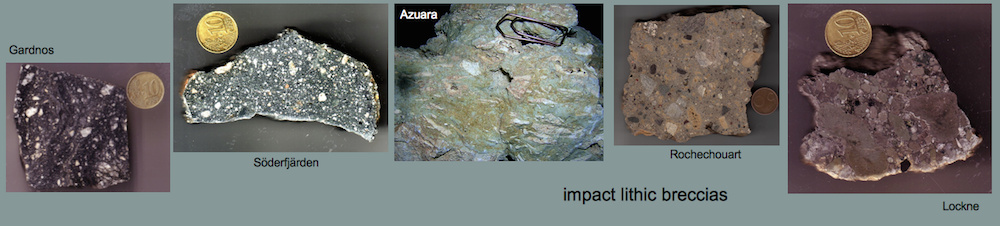

including images of more than 50 samples from our impact rock collection

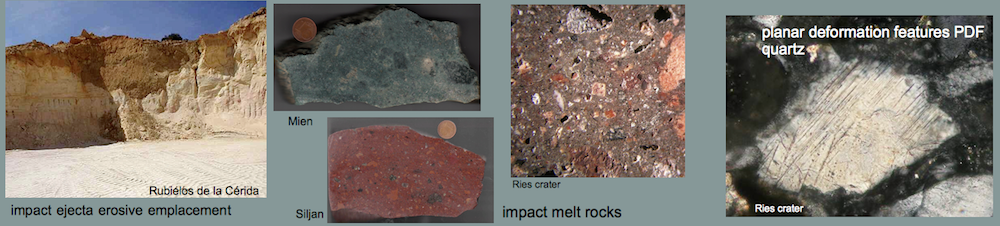

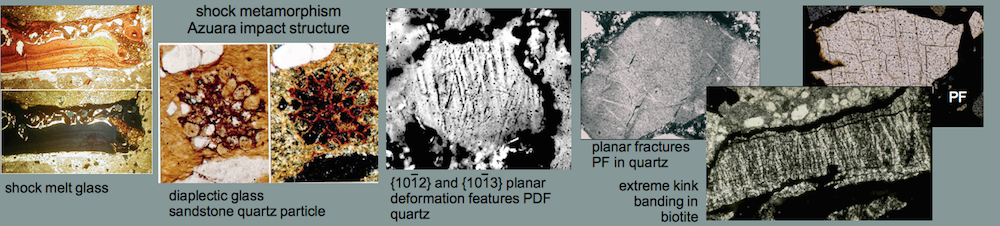

Melt rocks in and around impact structures in general originate from shock melting. For the formation of total rock melts, shock pressures in excess of roughly 60 GPa (600 kbar) are required.

According to an earlier classification of the IUGS Subcommission on the Systematics of Metamorphic Rocks, Study Group for Impactites, impact melt rocks are crystalline, semihyaline or hyaline rocks which have solidified from shock-produced impact melt und which contain variable amounts of clastic debris. [“hyaline” means glass-like, transparent.]. Meanwhile, the IUGS classification underwent some modifications (not exactly for the better) which we address in the Introduction to the impactite pages.

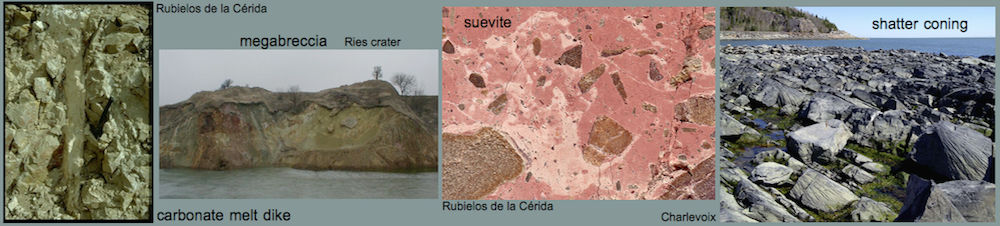

A clear distinction between impact melt rocks and impactites of the suevite type (see the Suevite page) is sometimes difficult and partly a matter of scale. Different from impact melt rocks, suevites are polymict impact breccias with a clastic matrix and mineral clasts in various stages of shock metamorphism including cogenetic impact melt particles which are in a glassy or crystallized state (IUGS definition). With regard to the impact cratering process, a formation of “pure” melt rock bodies and “pure” suevite bodies may take place largely, however a mixing to a certain degree and transitions are clearly to be expected. A typical example is given by the suevite of the Ries impact structure hosting large amounts of clasts that with regard to the IUGS definition are impact melt rocks (the so-called Ries glass bombs). Below, we show typical examples of this impact melt rock and also an image of the Polsingen impact melt rock that originally was considered a special variety of a Ries suevite breccia.

Impact melt rocks may originate also from frictional melting in strong dynamic metamorphism (pseudotachylites). From the very high dislocation velocities and extremely high pressures rocks are undergoing in the excavation stage of impact cratering the production of frictional rock melt is easily understood. Beside their occurrence in impact structures, pseudotachylites may be formed also tectonically.

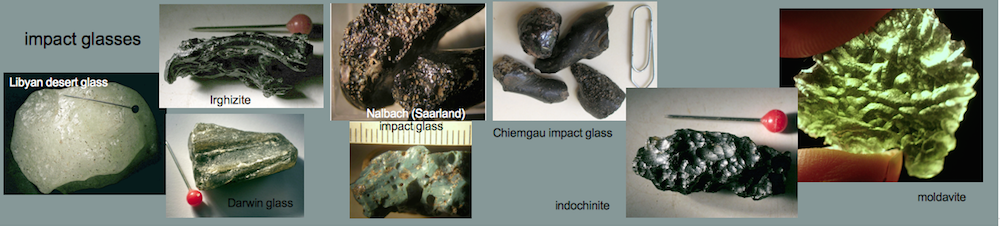

In rare cases, impact melts and melt rocks may be produced when excavated material passes through the superheated impact explosion cloud (vapor plume). A further possibility is currently discussed in relation with the occurrence of the Libyan desert glass. Model calculations suggest the silica glass, more or less melted desert quartz sand, has been formed in a giant air burst on explosion of the impactor above ground which can explain the search for a crater without any result.

A similar explanation may apply to the Darwin glass scattered over an area of about 400 km² in Tasmania, Australia. Although a 1.2 km-diameter depression, the Darwin crater, is considered to be related with the glass, the great quantity and the widespread occurrence seem to be unique and hardly compatible with a “normal” impact cratering process.

A special group of natural glasses very probably related with impact are tektites that occur in several strewn fields on the earth. Although a formation in the very beginning of the contact and compression stage of impact cratering is widely favored by scientists, also solid objections have been raised.

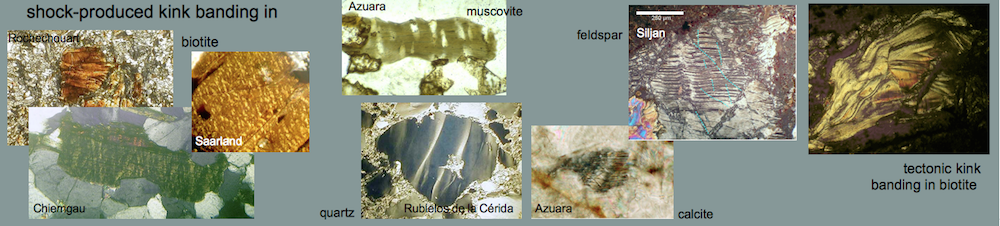

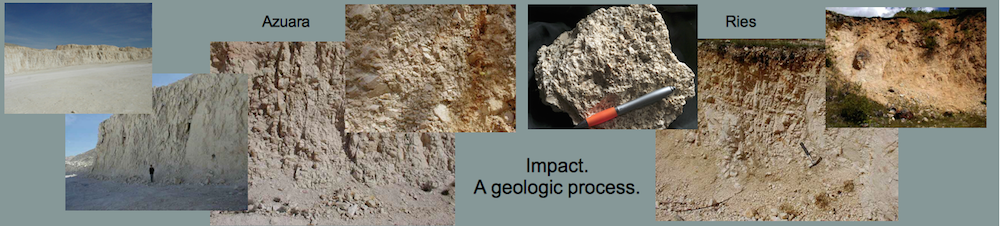

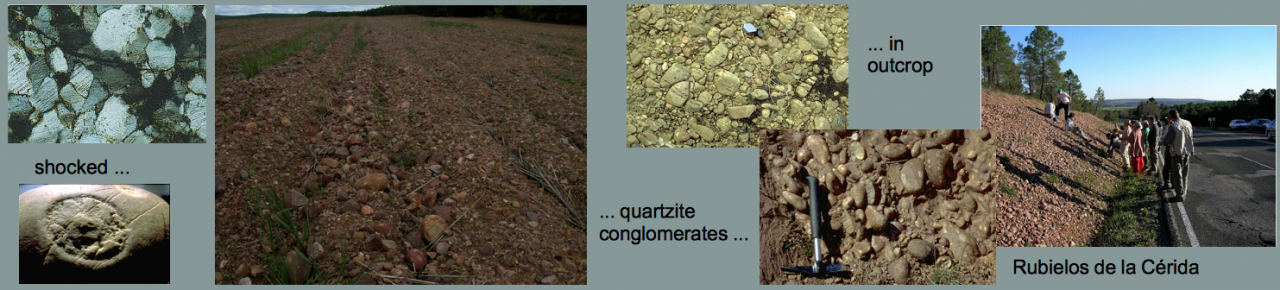

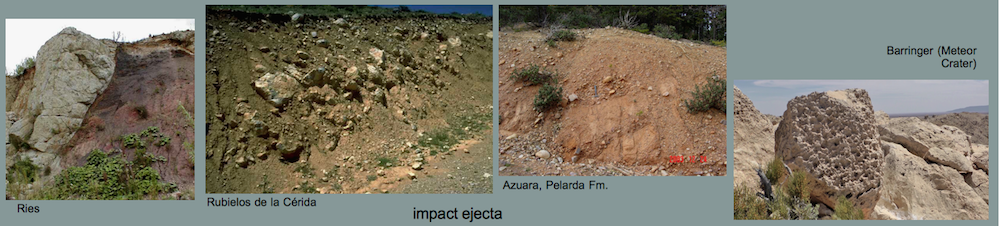

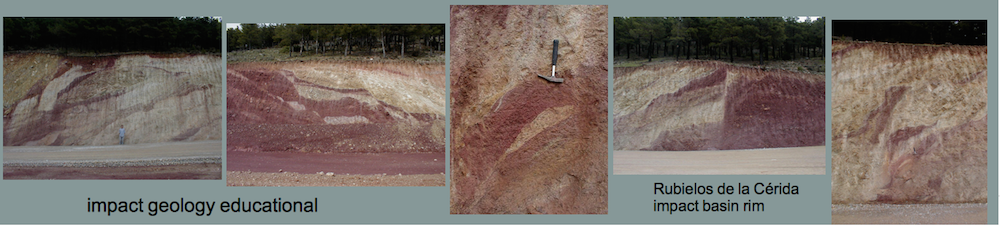

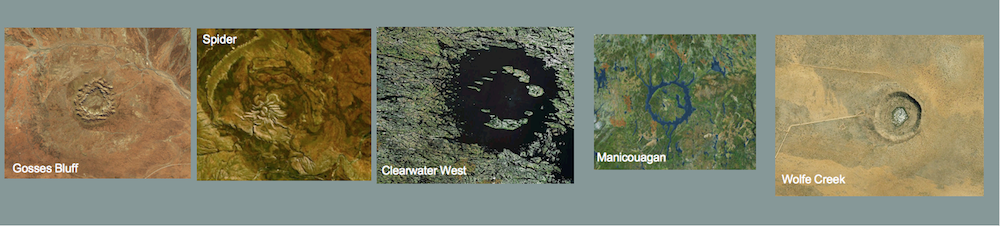

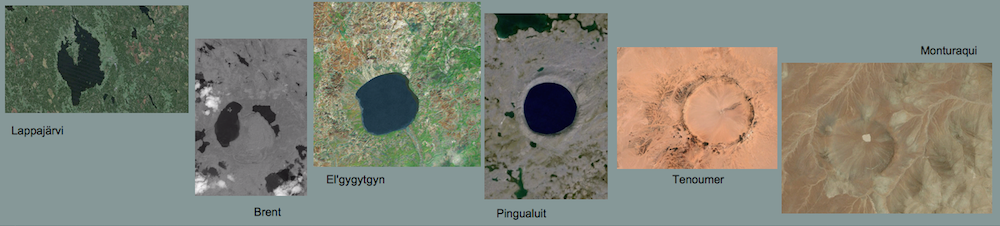

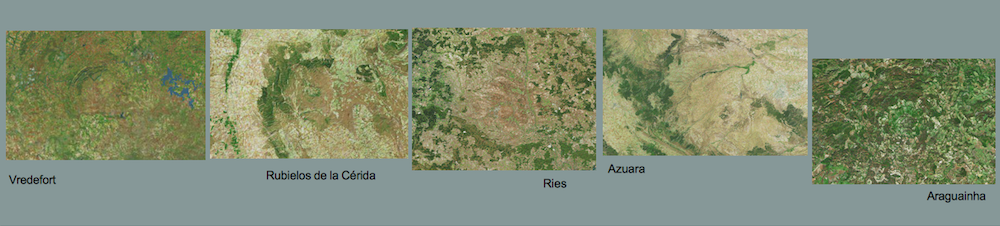

On this page, we show impact melt rocks, impact glasses and pseudotachylites from different impact structures and impact locations (Sudbury, Ries, Rochechouart, Dellen, Sääksjärvi, Siljan, Lappajärvi, Mien, Lake Hummeln, Paasselkä, Vredefort, Charlevoix, Henbury, Azuara, Rubielos de la Cérida, Zhamanshin, Lonar Lake, Dhala, Tenoumer, Aouelloul, Chapadmalal, Monturaqui, Libyan desert, Darwin crater, Chiemgau impact strewn field).

_________________________________________________________

Click on the images for blowup.

________________________________________________________

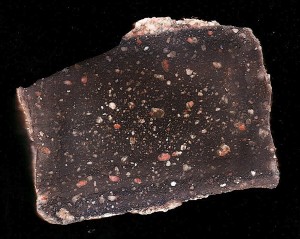

Fig. 1. Mien (Sweden) impact structure; impact melt rock; polished section <13 cm>.

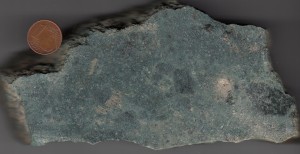

Fig. 2. Mien (Sweden) impact melt rock, green variety; sawed surface.

Fig. 3. One more variety of Mien (Sweden) impact melt rocks; polished section.

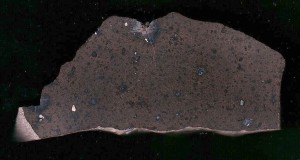

Fig. 4. Lappajärvi (Finland) impact structure; impact melt rock; kärnäite, polished section.

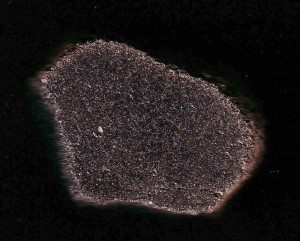

Fig. 5. Sääksjärvi (Finland) impact structure; impact melt rock; polished section <12 cm>.

Fig. 6. Sääksjärvi (Finland) impact structure; impact melt rock; sawed surface.

Fig. 7. Dellen (Sweden) impact structure; impact melt rock, dellenite, polished section <8 cm>.

Fig. 8. Impact melt rock from the Suvasvesi South impact structure (Finland).

Fig. 9. Impact melt rock from the Siljan ring impact structure, Sweden. The classification is not quite clear, and the impactite may as well be termed a suevite or a transition between both.

Fig. 10. Siljan ring, Sweden, impact structure; impact melt rock.

Fig. 11. Impactite from the 10 km-diameter Paasselkä impact structure (Finland). Probably an impact melt rock. See http://www.lpi.usra.edu/meetings/lpsc2003/pdf/1571.pdf

Fig. 12. Another impact melt rock variety from the Paasselkä impact structure, Finland.

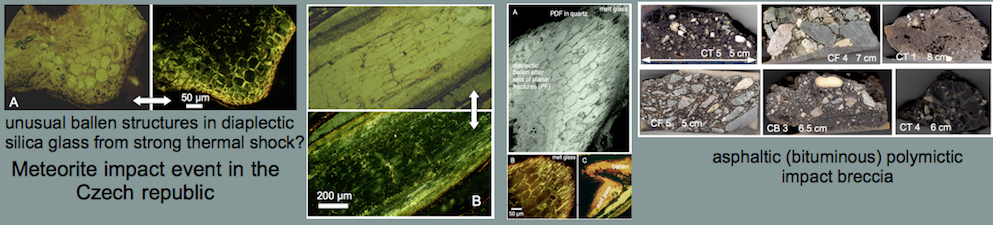

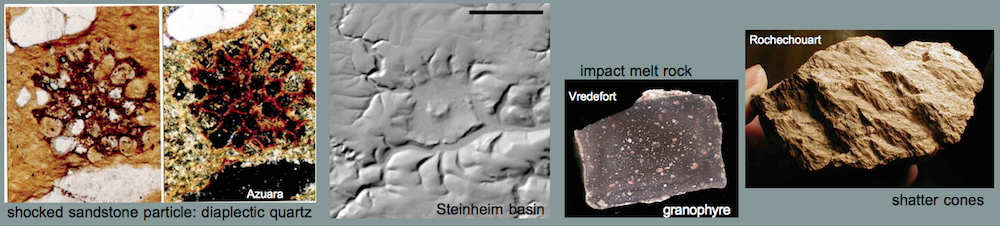

Vredefort (South Africa) impact melt rock

Fig. 13. Impact melt rock (granophyre), Vredefort impact structure (South Africa); polished section, <12 cm>.

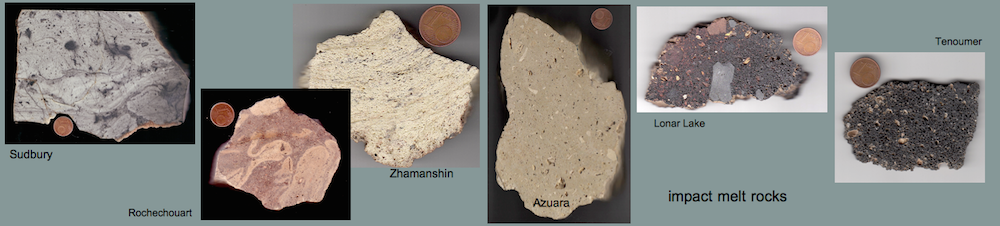

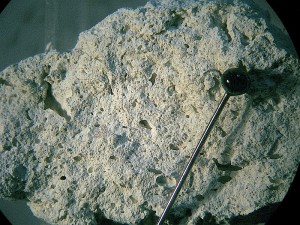

Tenoumer (Mauretania) impact melt rock

Fig. 14. Impact melt rock from the 1.9 km-diameter Tenoumer impact crater in Mauretania. Its Pleistocene age is estimated to be about 20,000 years.

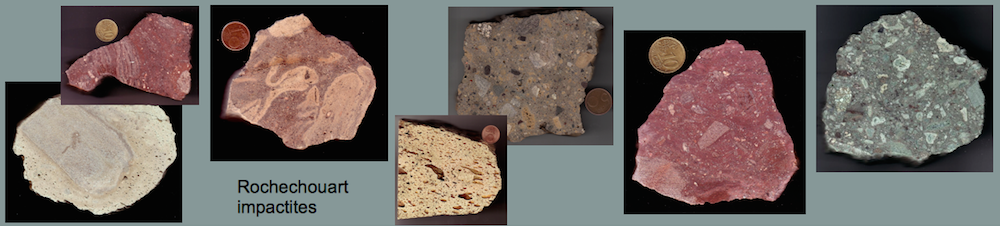

Rochechouart (France) impact melt rocks

Figs. 15-17. Various aspects of the impact melt rock from Babaudus, Rochechouart impact structure (France). Fig. 15. The melt rock sample (polished section, <17 cm>) contains a large gneiss fragment.

Fig. 16. Impact melt rock, Rochechouart impact structure. The strongly vesicular matrix is practically free of clasts.

Fig. 17. Impact melt rock, Rochechouart impact structure.

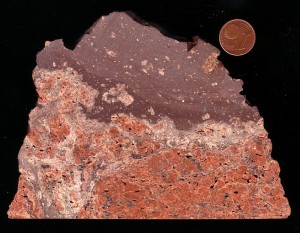

Sudbury (Canada) impact melt rock

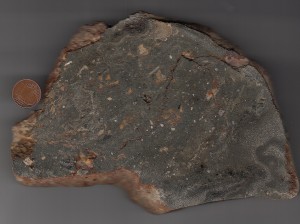

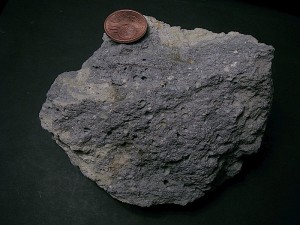

Fig. 18. Impact melt rock, Sudbury, Canada. Polished section. Coin diameter 16 mm.

Ries crater (Nördlinger Ries) impact melt rocks

(suggested link: https://www.impact-structures.com/impact-germany/the-ries-impact-structure-germany/)

Fig. 19. Impact melt rock, Ries (Germany); polished section <13 cm>. Formerly, this impact melt rock was considered a suevite (Polsingen “suevite”).

Fig. 20. Ries glass bombs separated from suevite by weathering; Heerhof occurrence. The “bombs” are aerodynamically shaped melt rock clasts that on landing were embedded in the suevite masses. Glassy, non-recrystallized, and recrystallized melt rock clasts are distinguished.

Fig. 21. Fragment of a Ries glass bomb (dark) in suevite. Aumühle quarry.

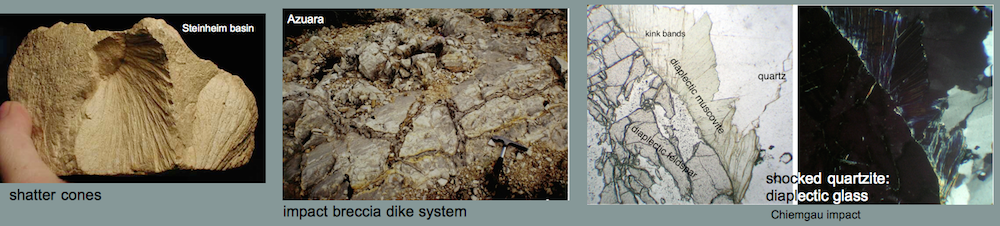

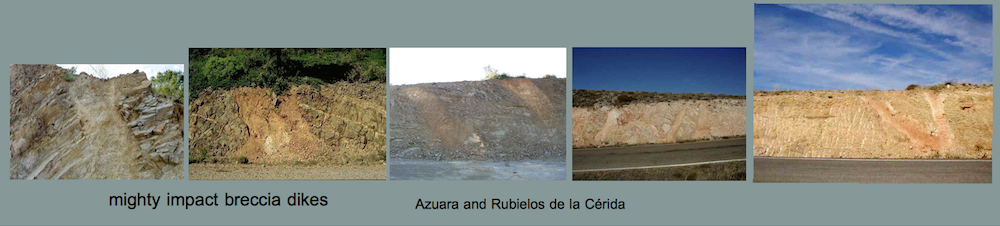

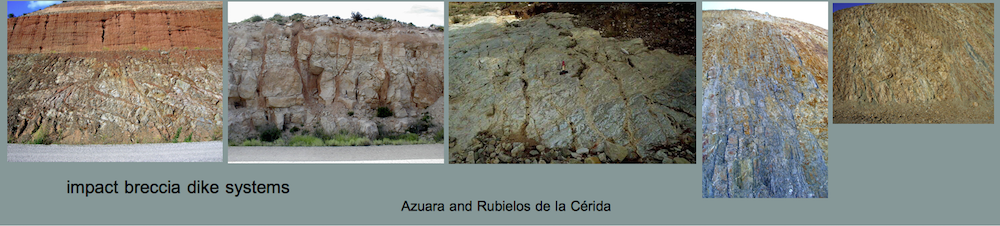

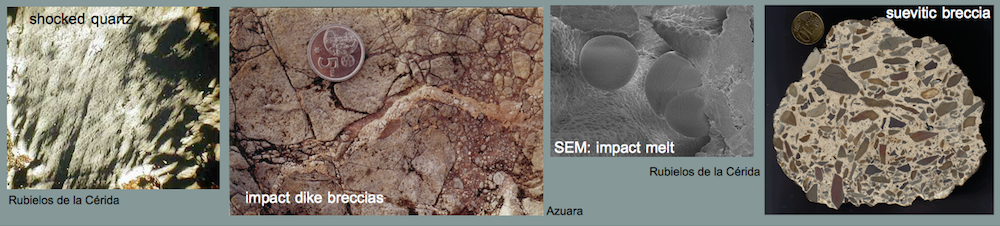

Melt rocks from the Azuara (Spain) impact structure

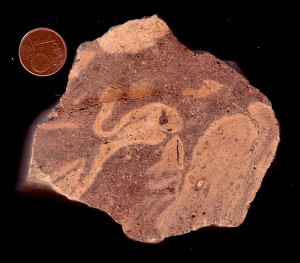

Fig. 22. Azuara impact structure (Spain): Impact melt rock, Almonacid de la Cuba variety. The matrix is considered to have solidified from a carbonate melt.

Fig. 22-1. Detail of the Almonacid de la Cuba melt rock. The in part strongly vesicular limestone clasts obviously underwent partial melting or/and decarbonization. Click on the image for enlarging.

Fig. 23. Azuara impact structure (Spain): Carbonate melt rock from Jaulín.

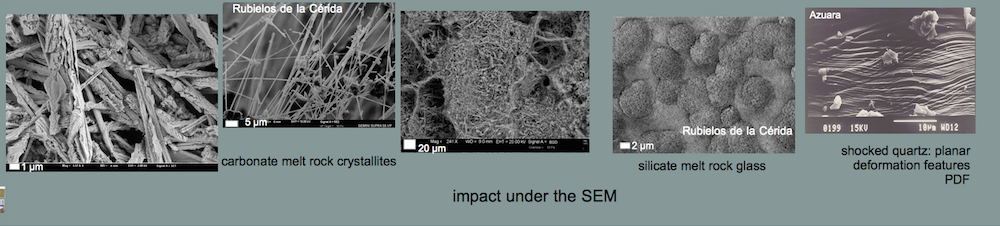

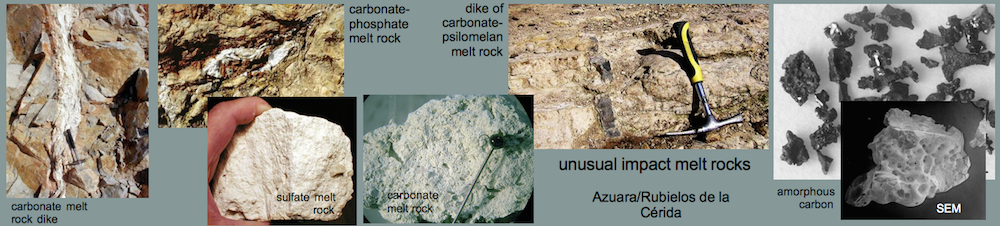

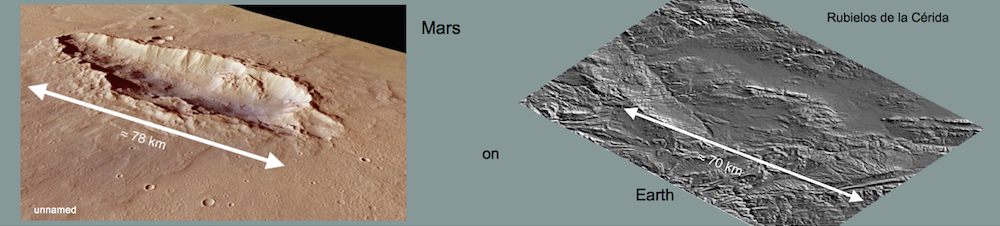

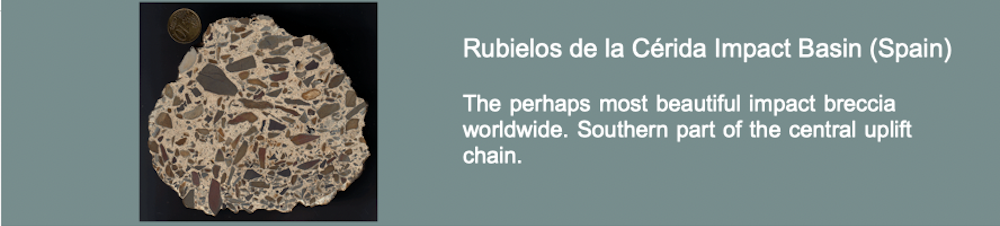

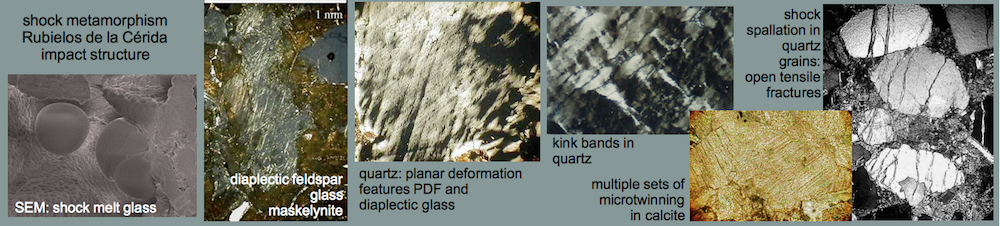

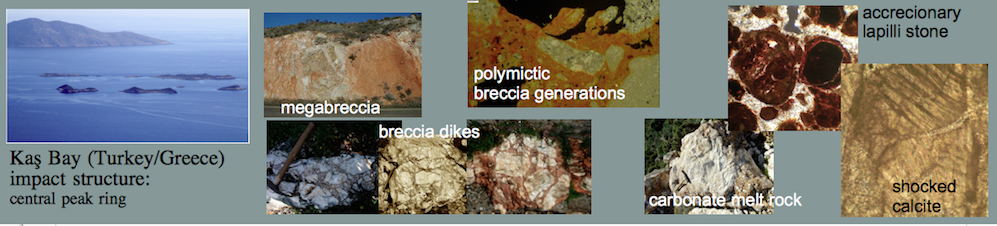

Melt rocks from the Rubielos de la Cérida (Spain) impact basin

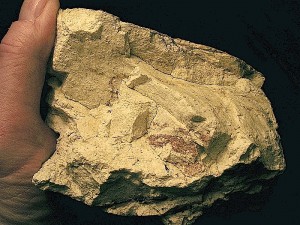

Fig. 24. Rubielos de la Cérida (Spain): The impact melt rock is composed of more than 90% pure glass from melted shale. Regional geologists from the Zaragoza university and, for whatever reason, also M.R. Rampino without having performed any analysis considered this melt rock full of shock effects a volcanic ash (!). For a detailed description click here.

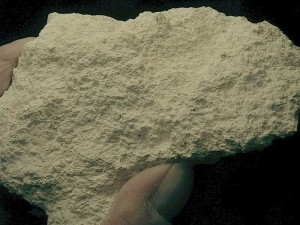

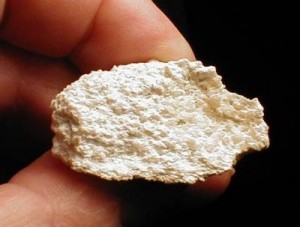

Fig. 25. Impact carbonate melt rock. Rubielos de la Cérida impact basin, central uplift chain, near Bueña. The density of this very light material occurring as big blocks in a limestone quarry is 1.2 cm³. Because of the impact-induced enormous comminution of the limestones and dolostones in the central uplift chain quite a few quarries have been located there making use of an easy exploitation. More about impact carbonate melt rocks can be read here.

Fig. 25-0. Blocks of relic carbonate melt rock intercalated in heavily shattered Jurassic limestones. Rubielos de la Cérida impact basin, central uplift chain, near Bueña.

Fig. 25-0. Blocks of relic carbonate melt rock intercalated in heavily shattered Jurassic limestones. Rubielos de la Cérida impact basin, central uplift chain, near Bueña.

Fig. 25-1. Close-up of the melt rock in Fig. 25.

Fig. 26. Rubielos de la Cérida (Spain): Probably a sulfate melt rock. The highly porous white matrix is chemically CaSO4, and the embedded quartzite fragments are in part strongly shocked. For a more detailed description click here.

Fig. 27. Rubielos de la Cérida (Spain): Carbonate-phosphate melt rock exhibiting liquid immiscibility of carbonate and phosphate melt. For a more detailed description click here.

Fig. 28. Rubielos de la Cérida (Spain): Melt glass from the central-uplift chain. Both a shock-produced melt or a formation by extreme dynamic metamorphism in the cratering process (pseudotachylite) are discussed. More can be read here.

Henbury impact melt rock

Fig. 29. Impact melt rock from the Henbury, Australia, crater field. For Henbury, rock melting by an airburst has been suggested:

https://gsa.confex.com/gsa/2010AM/finalprogram/abstract_182635.htm

Chapadmalal (Argentina) impact melt rock

Fig. 30. The peculiar glass (“escoria”) forms a layer in the Chapadmalal Formation near Mar del Plata, Argentina, and is related with a 3.3-Ma impact. A crater has so far not been identified.

Monturaqui (Chile) impact melt rock

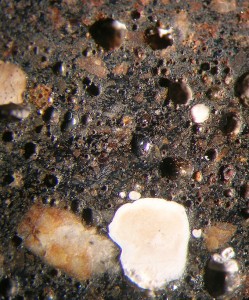

Figs. 31-32. Impactite from the 350 m-diameter, about 660,000 years old Monturaqui impact crater in Chile. The melt rock character is to be seen in the close-up image.

Figs. 31-32. Impactite from the 350 m-diameter, about 660,000 years old Monturaqui impact crater in Chile. The melt rock character is to be seen in the close-up image.

Lonar Lake (India) impact melt rock

Fig. 33. Impact melt rock from the 1.8 km-diameter Lonar Lake impact structure in India. The impact occurred in basaltic rocks, and thus the Lonar Lake impact is considered a model impact for craters on Mars and Moon. Age estimates are about 50,000 and about 650,000 years, respectively.

Dhala (India) impact melt rock

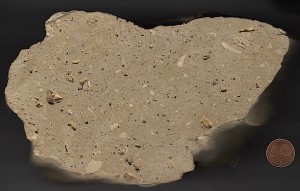

Fig. 34. Impact melt rock from the 11 km-diameter highly eroded Dhala impact structure in India. Dhala, with an estimated age of about 2,000 Ma, is the third oldest terrestrial impact structure.

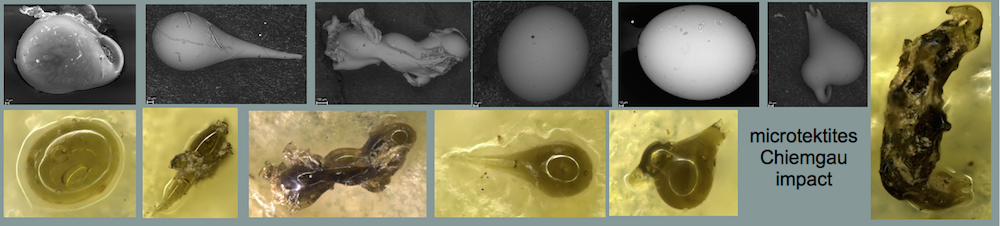

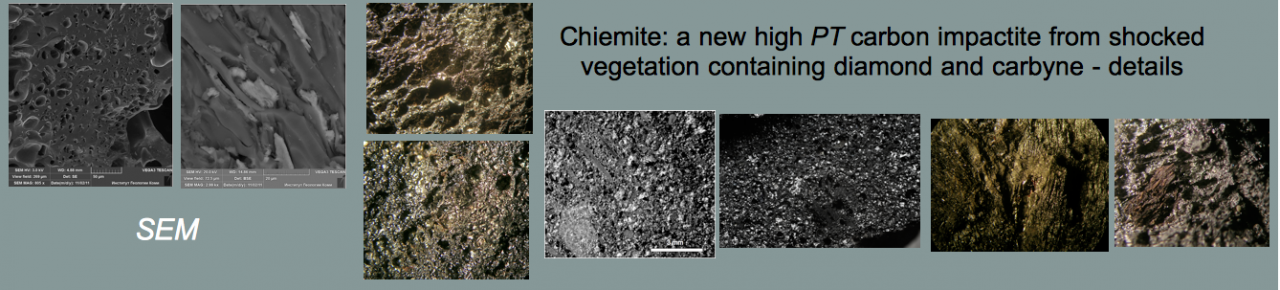

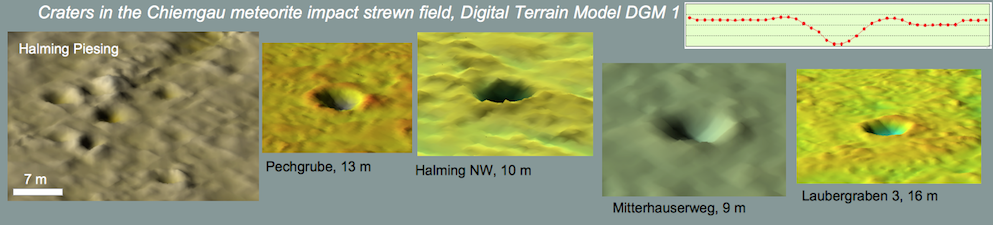

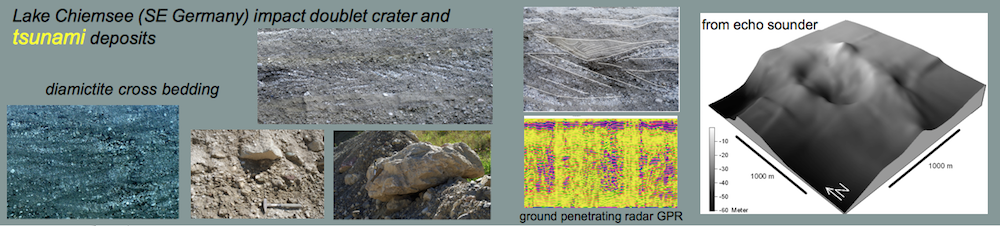

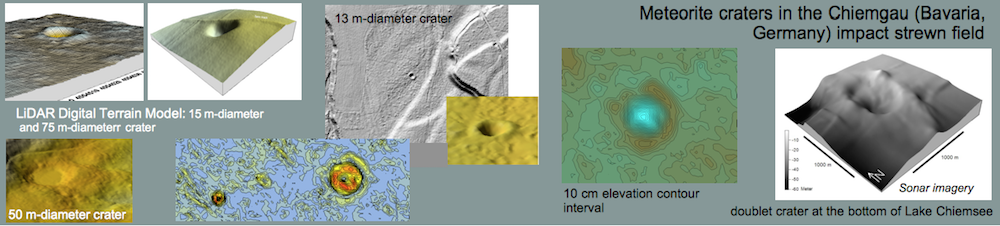

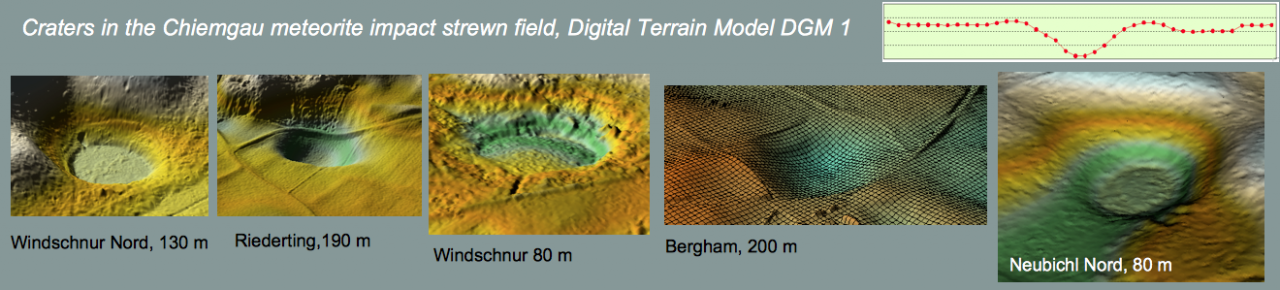

Melt rocks from the Holocene Chiemgau impact (suggested link: http://www.chiemgau-impact.com/)

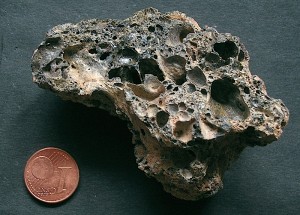

Fig. 35. Pumice-like melt rock from the Tüttensee crater, Chiemgau impact strewn field.

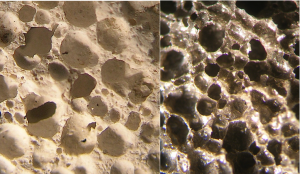

Fig. 35-1. Pumice varieties (carbonate white, silicate dark) from the Lake Chiemsee shore; probably impact melt rocks from the suggested doublet impact crater at the bottom of Lake Chiemsee, Chiemgau impact event. A full article may be clicked HERE.

Fig. 35-2. Close-up of the white (carbonate) and grayish (silicate) pumice melt rock varieties shown in Fig. 35-1.

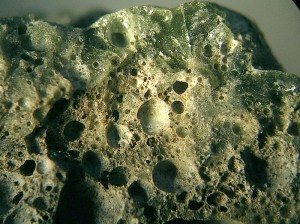

Fig. 36. Impact melt rock from the Chiemgau impact strewnfield. In the upper part, the pumice-like melt rock merges into dense greenish glass. The field is 14 mm wide.

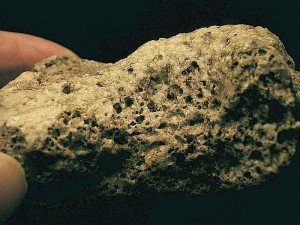

Fig. 37. Vesicular, foamy impact melt rock (Alpine cobble) from the Chiemgau impact strewn field. From crater #004. For the #004 and other craters and related melt rocks of the Chiemgau impact strewn field an impact air burst has been discussed.

Fig. 38. Chiemgau impact strewn field, crater #004: fused cobbles from Quaternary gravel plain target. Because of a halo of extreme temperature influence around the 11 m-diameter crater an impact airburst may have happened in the Chiemgau impact event.

Fig. 39. Chiemgau impact strewn field, crater #004: gneiss cobble from the Quaternary gravel plain target nearly completely melted to glass. Read more in captions of Figs. 37, 38.

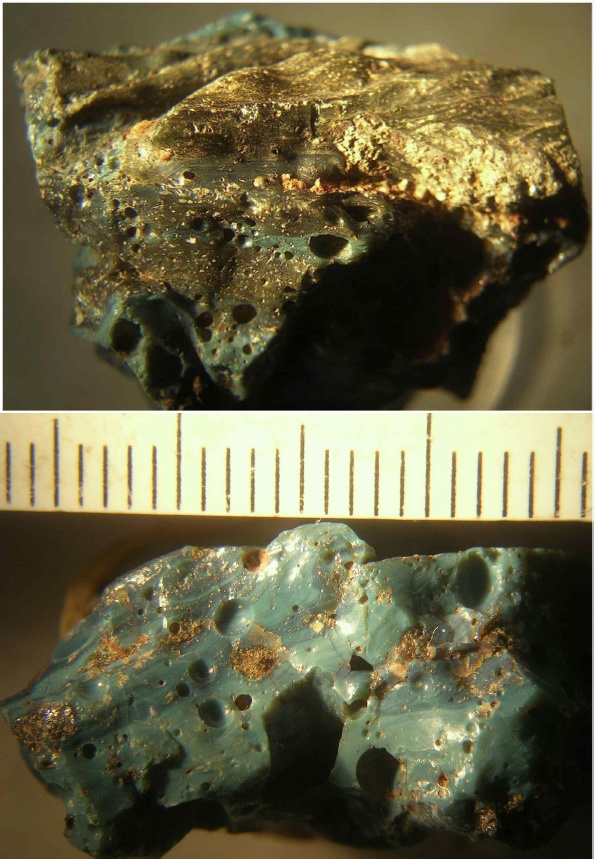

Fig. 40. A very peculiar impact melt formation is found widely spread in the crater strewn field of the Chiemgau impact in the form of silicate cobbles and boulders (quartzites, gneisses, sandstones) that are vitrified all around. Here we show a broken quartzite cobble with a surface of colorless, greenish and brownish-black glass (upper) and the fracture plane that is partially covered with dark glass (lower). The coating glass is in most cases very thin, a fraction of a millimeter only, which can be seen in the close-up of Fig. 41. The cobble has been sampled in the vicinity of the Mauerkirchen crater.

Fig. 41. The fracture plane exhibits how thin the glass coating is. This proves that the heat build-up to melt the rock material must have been very short and at the same time extremely high excluding any furnace processes. The impact process can give a reasonable explanation for the formation of the glass. The alpine cobbles were excavated from the ground and ejected into the superheated impact explosion cloud where they experienced their short-term heating-up before they landed on the ground, frequently already significantly chilled below the melting point. The latter can be concluded from the fact that many of the vitrified cobbles do not show any contact imprints in the glass coating.

Another explanation has been given by the geochemist and impact researcher Christian Koeberl from the Vienna university. When the local historians and discoverer of the Chiemgau impact had asked him for an explanation for the formation of these peculiarly vitrified cobbles from the pre-Alps gravel plain, he in a written communication stated the possibility that the melt coating of the cobbles could have originated from strong tectonic movements in the Alps.

Zhamanshin (Kazakhstan) impact melt rock

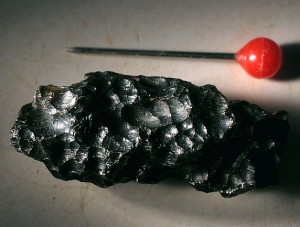

Fig. 42. Impact melt rock from the Zhamanshin impact structure in Kazakhstan. The Pleistocene 14 km-diameter structure is estimated to be about 900,000 years old.

Special impact glasses

Fig. 43. Libyan desert glass. For the (?) impact glass found over large areas in the Libyan desert up to tens of kilometers no impact crater has so far been identified and, hence, a melting of the desert sand by a meteoritic airburst has been suggested, similar to the outcome of the Trinity nuclear explosion (see Fig. 51).

Fig. 44. Irghizite impact glass from the Zhamanshin impact crater, Kazakhstan.

Fig. 45. Impact glass from the 390 m-diameter Aouelloul impact crater in Mauretania. The impact occurred about 3 million years ago.

Fig. 46. Darwin impact glass, Tasmania, Australia. The widespread (over 400 km²) occurrence of this natural glass is hardly compatible with the small size of the 1.2 km Darwin crater depression located in the strewn field of the glass, and a meteorite airburst may be considered responsible.

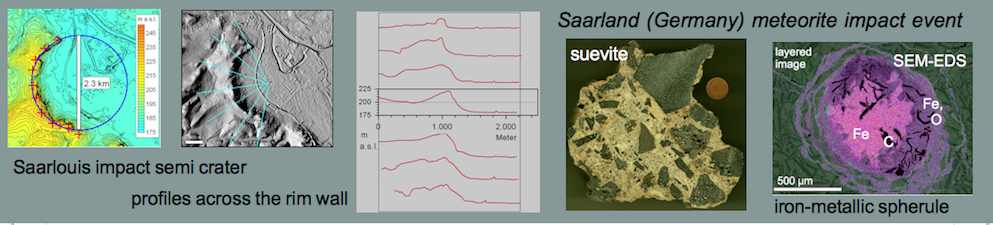

Impact glass – Saarland impact event

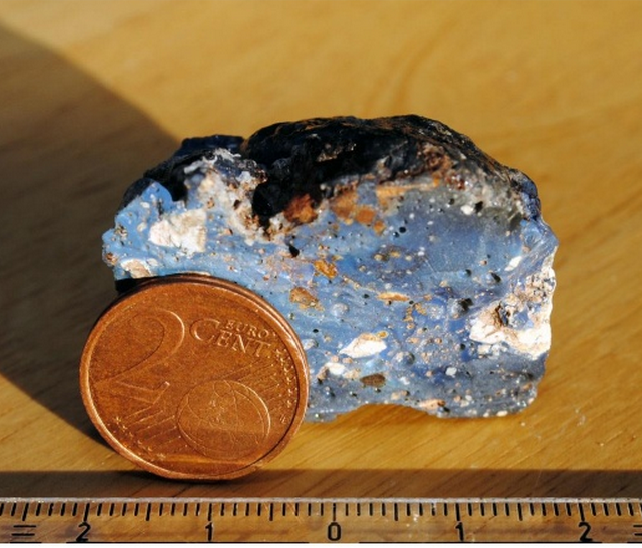

Fig. 46 – 1. Blue glass with shocked rock and metallic inclusions, Saarland impact. (image Berger 2014)

Fig. 46 -2. Glass fragments with banded color from the Saarland impact area. Millimeter scale. (Image Müller 2011).

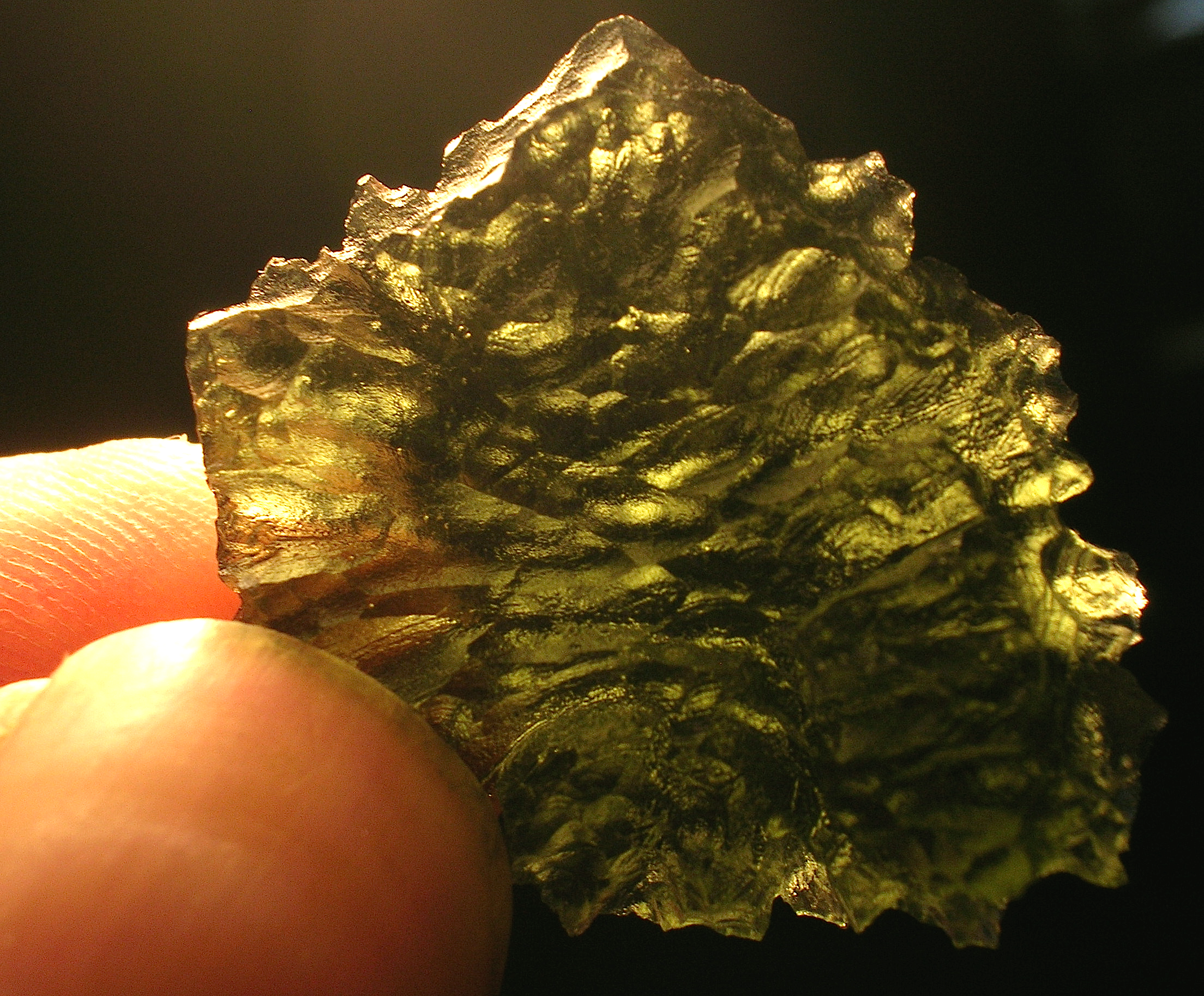

Tektites

Specimen courtesy of Martin Molnár.

Specimen courtesy of Martin Molnár.

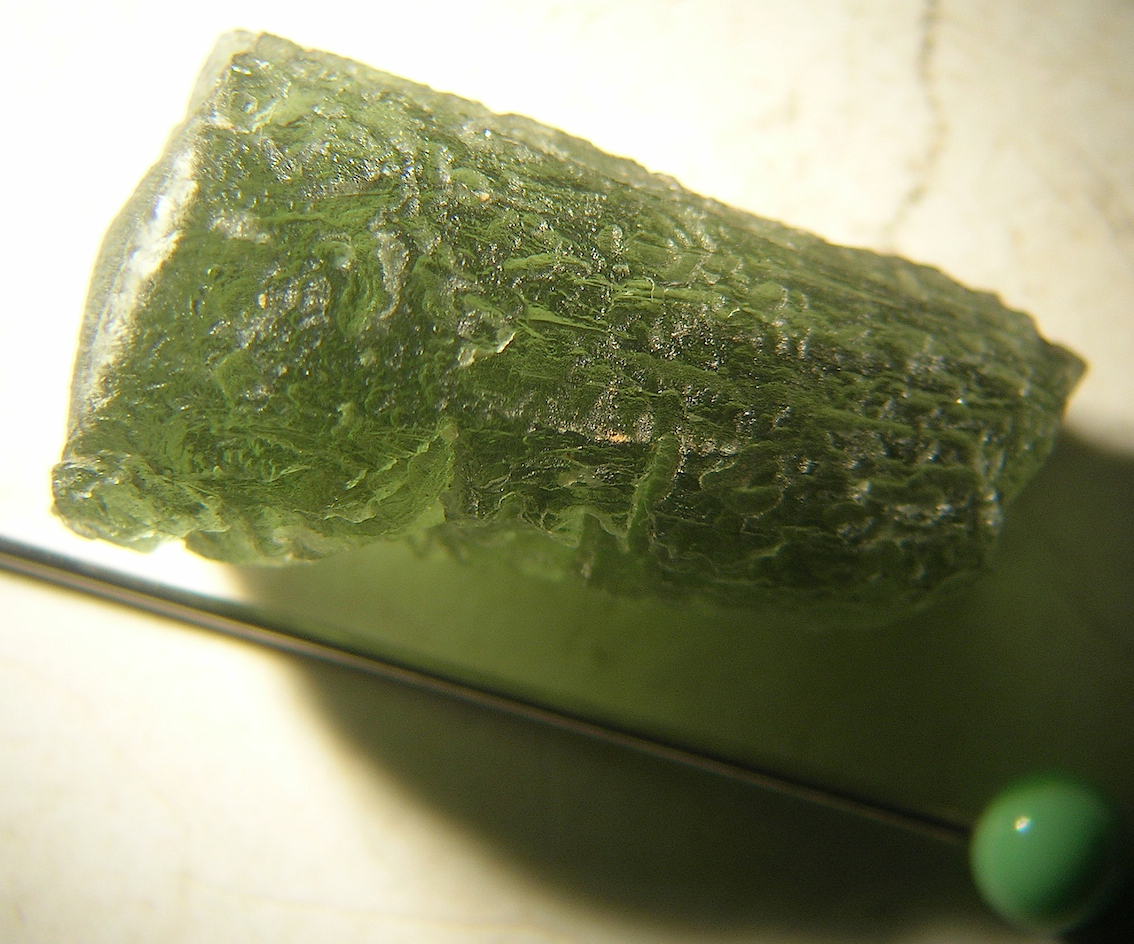

Fig. 47. Moldavites (Bohemia, Czech Republic). The moldavite tektites are the same age as the Ries impact structure. – Because of the rarity of beautiful specimens, which are traded also as gemstones, fakes made of ordinary glass are increasingly offered (especially in the internet).

Fig. 48. Tektite glass, javaite. From Kaliosso, Java.

Fig. 49. Tektite glass, indochinite. From Guang Dong, China.

Fig. 50. Tektite glass, indochinite. From Phang Daeng, Thailand. [Irghizite, Darwin, indochinite samples by courtesy G. von Berg]

Tektite-like glasses (Chiemgau and Saarland impacts)

Fig. 50 -1. Upper: Tektite-like glasses from the Chiemgau impact area. Lower: Twisted tektite-like glass bodies with flow structures from the Saarland impact (upper; see Fig. 50 -2) and the Chiemgau impact. (image Müller 2012).

Fig. 50 -2. Tektite-like glasses from the Saarland impact. (Image Müller 2012).

Fig. 50 -3. End fractures of the glasses in Fig. 50 1(lower) showing the vesicular internal texture. (Image Müller 2012).

NOT from impact: for comparison glass that formed in the Trinity explosion, the first detonation of a nuclear device (on July 16, 1945).

Fig. 51. Trinitite (Atomsite, Alamogordo Glass): Still radioactive glass from the ground in the Trinity nuclear explosion area. A similarity with some impact glasses can be stated (see, e.g., Fig. 36, glass from the Chiemgau impact).

Pseudotachylites

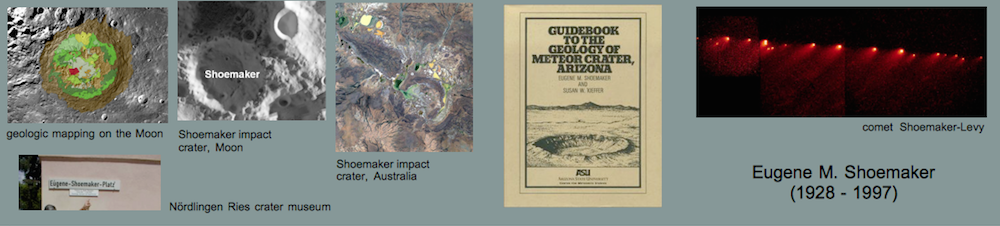

A tachylite is a black volcanic glass formed by the chilling of basaltic magmas. Early geologists in Vredefort identified something like it and called it pseudotachylite. According to a former definition of the IUGS Subcommission on the Systematics of Metamorphic Rocks, Study Group for Impactites, a pseudotachylite is a dike-like breccia which formed by frictional melting in the basement of impact structures and which may contain unshocked and shocked mineral and lithic clasts in a fine-grained aphanatic matrix. Meanwhile, the term “pseudotachylite” is no longer used in the IUGS classification which we comment in the Introduction.

Fig. 52. Pseudotachylite (the black veins), Vredefort (South Africa) impact structure; maximum size <19 cm>. Originally the Vredefort pseudotachylites were interpreted to have originated from endogenetic, seismic faulting or landslide processes.

Fig. 53. Pseudotachylite (the dark vein), Rochechouart (France) impact structure. The Rochechouart pseudotachylites are observed especially in the Champagnac quarry where they occur together with impact breccia dikes. A simple distinction is not always possible. Here we remind of the difference by definition: a breccia dike has a clastic matrix compared with the melt rock or glassy matrix of a pseudotachylite.

Fig. 54. Siljan, Sweden, impact structure; pseudotachylite in Järna granite. Sample by courtesy Jan-Olov Svedlund.

Fig. 55. Lake Hummeln pseudotachylite (the black veinlets). The 1.2 km-diameter Lake Hummeln depression is ranking as a probable impact structure.

Fig. 56. Pseudotachylite, Charlevoix (Canada) impact structure; polished section <12 cm>.

Natural melt rock of questionable origin: Köfelsite (also spelled Köfelsit, Koefelsite, Kofelsite)

Fig. 57. White Köfelsite glass from Köfels, Austria. The origin of the about 8,000 years old glass is disputed and has been attributed to volcanism, meteorite impact, to a giant landslide (“frictionite”) and an impact-triggered landslide. The landslide formation has largely been accepted.

Fig. 58. Dark, pumice-like Köfelsite. Köfelsite samples by courtesy H. Stehlik.

More links:

http://www.lpi.usra.edu/publications/books/CB-954/CB-954.intro.html

PDF download of Bevan M. French (1998): Traces of Catastrophe. A Handbook of Shock-Metamorphic Effects in Terrestrial Meteorite Impact Structures. LPI Contribution No. 954, 120 pp.

Jarmo Moilanen’s homepage on impact structures including a “List of impact structures of the world” and images of his impact rock collection.